Segmenting Comic book Frames

This post is based on my project in my Computer Vision class last semester

Introduction

As I was learning classical techniques in my Computer Vision class, I came across a blog post by Max Halford on extracting frames from comic books. He developed a very interesting algorithm where he applied Canny to detect the boundary of frames, filled holes and fit bounding boxes to contiguous regions.

This elegant algorithm did the job very well but had its shortcomings. For one, it didn’t handle arbitrary, un-aligned polygons and didn’t work on negative frames, which didn’t have a boundary of their own, but rather were defined by the boundaries of neighboring frames.

Given the hype around foundation models for segmentation such as SAM, I approached this problem by procedurally generating a synthetic dataset of comic books and finetuning SAM to detect the corner points of frames.

|

Procedural Comic Generator

There isn’t abundant data available for this problem. But that doesn’t mean that we should hold our head in our hands. A common technique that is widely used (see Erroll Wood’s work) is to procedurally generate training data.

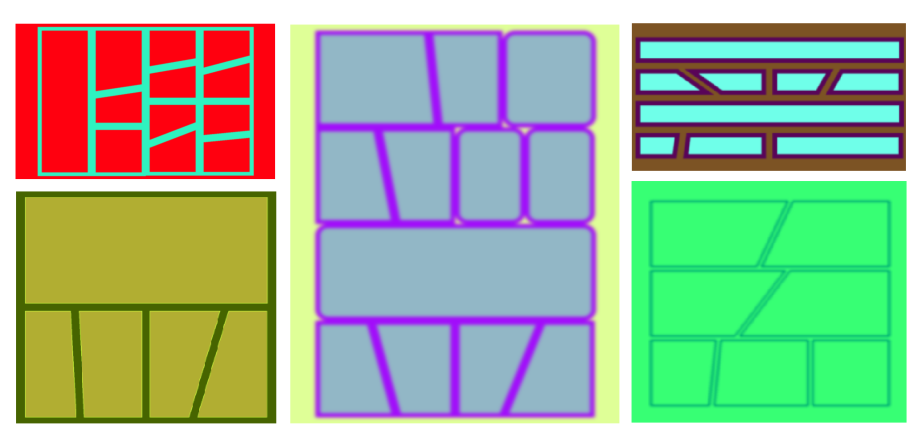

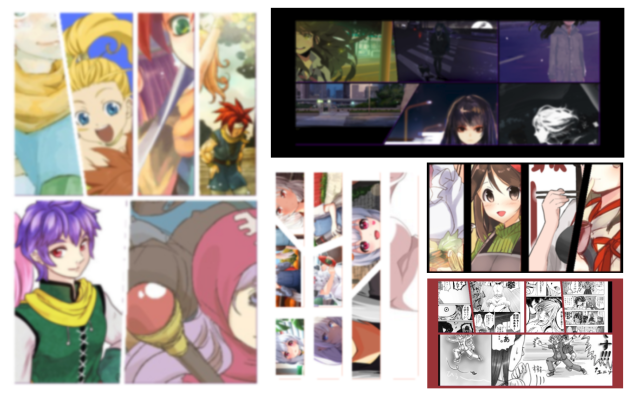

In our case, this means simulating comic books. Note, we don’t really need to make gripping animations and tell a story, we just need to generate panels that look like comics from 50,000 feet. In order to do this, I wrote a procedural generator of layouts and assigned random boxes on an empty image. I filled these boxes with images sampled from the Danbooru dataset.

In order to ensure that the sampled images were atleast semi-coherant, I used CLIP L/14 image encoder to create an image index. While choosing images for a particular page, I sampled one image at random from Danbooru and filled the rest of the boxes using it’s k-nearest neighbors.

With this procedural generator, I had complete control of the size, shape and boundary properties of the box, which I could set appropriately to simulate negative and polygonal frames.

|

|

Comic Segmentation

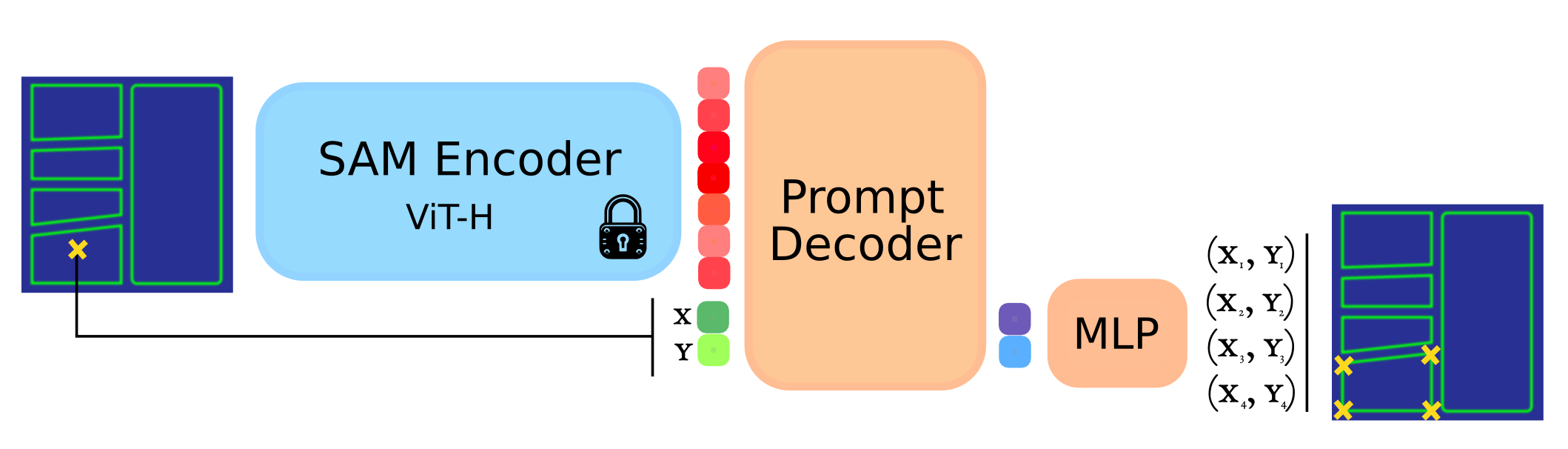

I used SAM as the backbone for my model. SAM is the state-of-the-art image segmentation model. It consists of a heavy, compute expensive image encoder and a light-weight decoder, which answers segmentation queries. The heavy encoder encodes an image only once, after which multiple segmentation queries are answered cheaply. This division of labor is particularly useful for deployment, where an enterprise serving a user can optimize for both speed and costs by keeping the heavy encoder inference on the cloud and using the user’s device for light-weight inference.

Since SAM predicts dense, per pixel mask, I modified it to predict points instead. An overview of the model can be seen below. The procedurally generated comic frame is fed to the image encoder (whose weights remain unchanged during training). A point is randomly sampled from a frame and given as a query/prompt. The light-weight decoder is trained to recover the corners of the frame.

|

I learned two lessons while training this model. Firstly, it was important to canonicalize the order in which the corners of the frame were predicted. Without this, the model got conflicting signals on the ordering of corner points and never converged. Secondly, it was important to use L1 instead of L2 loss since L2 optimized very quickly without improving the quality of predictions.

Evaluation

I compared my method against original SAM and Halford’s method. Note that Halford’s method is a bit disadvantaged in this comparison since my method also uses a query (set to the center of the ground truth frame to be predicted). Despite this, it is evident that our model trained on our procedurally generated dataset, generalizes on “real-world” comics (Pepper and Carrot abbrev. as P&C), coming close to Halford in the process. It beats Halford on procedurally generated dataset (abbrev. Pr), since this dataset is designed to expose the flaws in the method.

| Method | IoU (P&C) | PCK@0.1 (P&C) | L1 (P&C) | IoU (Pr) | PCK@0.1 (Pr) | L1 (Pr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.08 |

| Halford | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.47 |

| Ours | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.03 |

Here, IoU simply measures the area of intersection over union of the ground truth and predicted frames. PCK@0.1 refers to the percentage of times, the predicted frame corner lies within certain radius of the ground truth frame corner (0.1 refers to the radius as a percentage of the diagonal of the comic page). L1 is simply the L1 distance between ground truth and predicted frames.

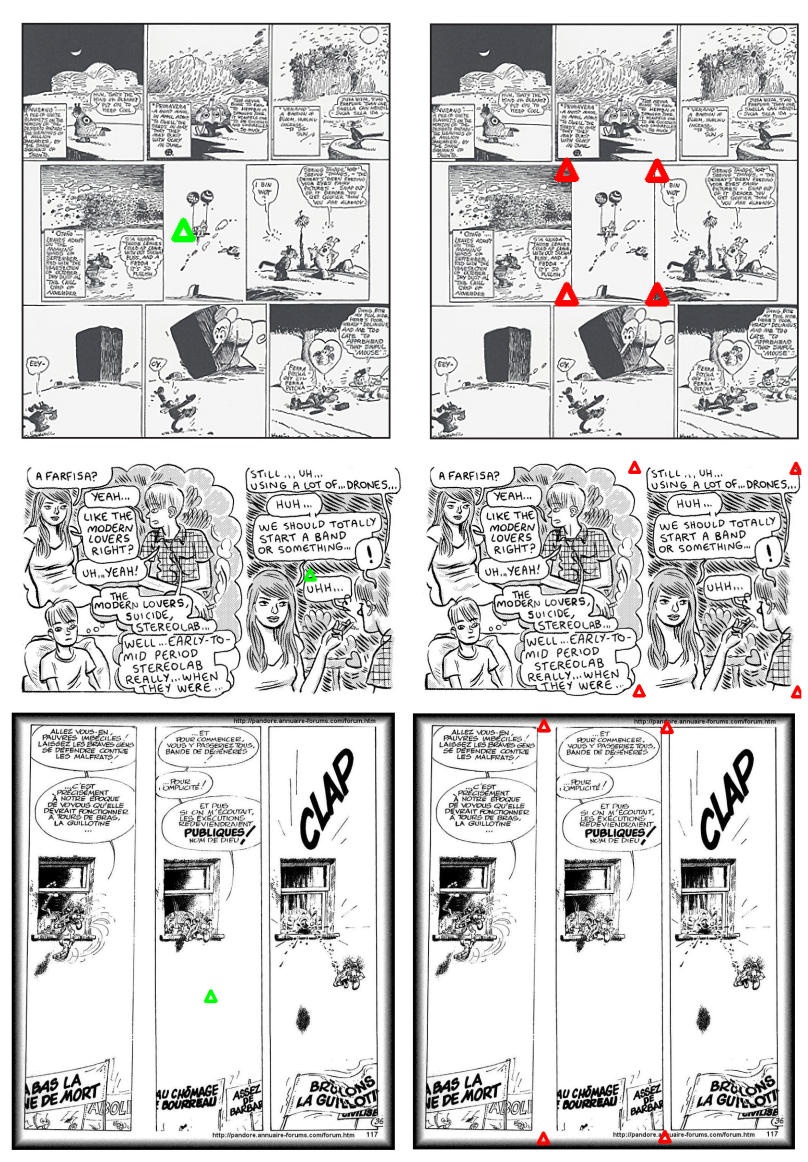

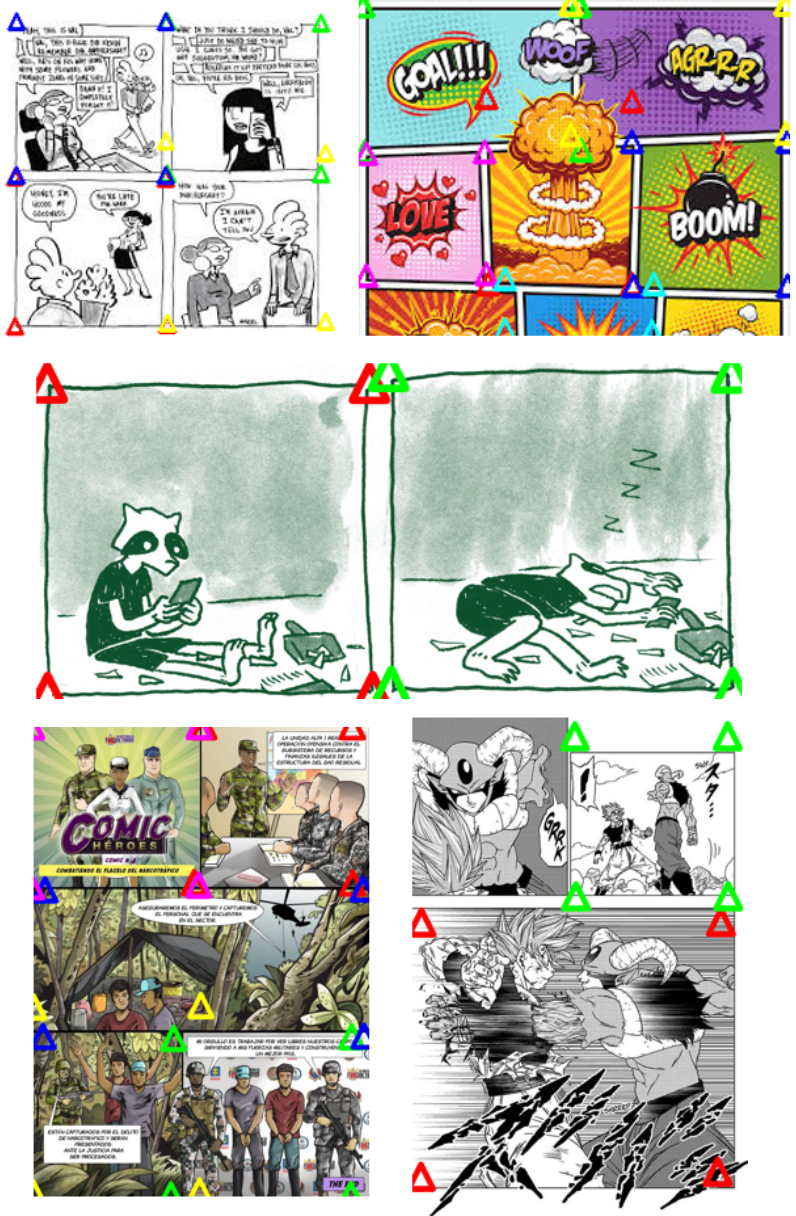

Below are some qualitative results which demonstrate that our method works on “real-world” comics. We run it in two modes. On the left, we interactively provide a query and the model produces the corners. On the right, we sample a bunch of query on the image, predict polygons and filter them using non-maximal suppression like the original SAM paper.

|

|

Final Thoughts

There are still shortcomings to my method and it can often fail for complex, cluttered comic pages. But still, I like this approach to designing algorithm over composing OpenCV functions because it is often easier to see how to improve the dataset than to design new heuristics. Once you do that, you almost have a guarantee that the Neural Network machinery will get you the results.

The annotated Pepper and Carrot dataset that I used for evaluation can be found in my drive link. All my code and checkpoints are available in my Github Repo. If you think of any improvements to my approach, feel free to reach out!